By Brie Reid

Throughout evolution, humans have experienced periods of feast and famine. Growing evidence suggests that adversity and height growth stunting early in childhood increases risk for early onset puberty (in girls), obesity, and poorer mental health later in life. Researchers think that this is the case because in the first 1,000 days after conception, our very young, growing bodies determine whether the environment we are growing up in has a lot of resources or has little resources. In this way, our bodies “calibrate” to the environment we expect to grow up in. However, researchers think that early physical adaptations to harsh environments with very little resources may increase later risks of obesity, early onset puberty in girls and metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, because our bodies do not anticipate a shift from resource-poor to resource-rich environments.

Throughout evolution, humans have experienced periods of feast and famine. Growing evidence suggests that adversity and height growth stunting early in childhood increases risk for early onset puberty (in girls), obesity, and poorer mental health later in life. Researchers think that this is the case because in the first 1,000 days after conception, our very young, growing bodies determine whether the environment we are growing up in has a lot of resources or has little resources. In this way, our bodies “calibrate” to the environment we expect to grow up in. However, researchers think that early physical adaptations to harsh environments with very little resources may increase later risks of obesity, early onset puberty in girls and metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, because our bodies do not anticipate a shift from resource-poor to resource-rich environments.

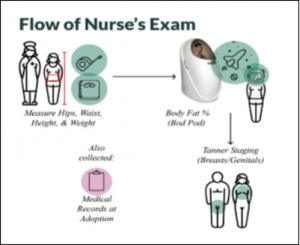

We tested this hypothesis with 283 youth aged 7-14 years who participated in the first year of the Puberty Study. We looked at data collected from adopted children’s first medical clinic visit post-adoption and we also looked at data collected from the nurse’s exam, see Figure 1, in the Puberty Study.

Growth

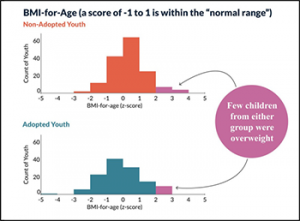

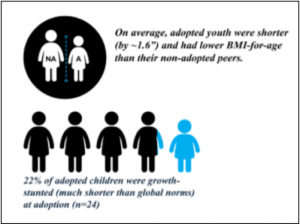

On average, adopted youth were shorter (by ~1.6”) and had lower BMI-for-age than their non-adopted peers. Adopted youth also tended to have lower numbers of body fat percentage. On average, both groups of youth were within normal ranges of height, weight, and body fat. There were no differences in waist-to-hip ratios or waist-to-height ratios between groups. A key finding was that there were very few overweight or obese youth in either the adopted or the non-adopted group, which surprised us because nearly one in three children ages 10 to 17 are overweight or obese in America.

Pubertal Development

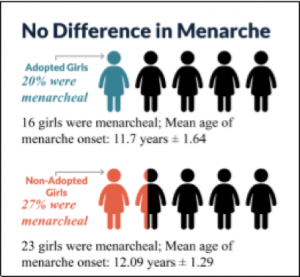

We found that pubertal status was determined by being older and being heavier for your age. This is just what is expected as bodies typically put on fat to support the pubertal changes in growth. What surprised us is that we found no evidence that the internationally adopted children, many of whom had experienced relatively harsh conditions in orphanages prior to adoption, were going through puberty earlier than the children born into their Minnesota family as seen in Figure 2. We did not see this for either boys or girls.

Previously Height Stunted Adopted Youth Results

Previously height-stunted youth adopted internationally, though still shorter on average, were not found to be at greater risk for high BMI and were also less likely to be in later puberty stages.

Previously height-stunted youth adopted internationally, though still shorter on average, were not found to be at greater risk for high BMI and were also less likely to be in later puberty stages.

Our conclusion?

Early life adversity and height-growth stunting early in life do not always lead to early puberty or obesity in later childhood or adolescence!

Early removal from adversity or later contexts of highly-resourced homes could protect children from long-term impacts on their BMI and the timing of puberty. Subsequent waves of longitudinal data collection will provide a window into pubertal timing across three years to determine if adopted and previously height-stunted youth experience a different pubertal development tempo than non-adopted peers. This tempo could also impact body fat as our sample of participants get older.

Multiple years of follow-up and more precise measures of where children store fat on their bodies and metabolic health are our next steps to ensure we understand the full picture of growth and pubertal development in the context of early challenging life conditions.

New Study Opportunity: Early Stress, Growth, and Metabolic Health Study

New research suggests that early life stress and early height stunting can contribute to later health by impacting the growth, body fat composition, and cardiovascular health. This may mean that experiences in childhood influence our health in adulthood. If we can identify these changes early on, then we can develop interventions to hopefully prevent later health problems.

In the Puberty Study, we did not find that children who were growth-stunted at adoption were becoming overweight as they approached adolescence, so the question for heart health is actually where does the body put its fat. Deep visceral (belly) fat is a risk factor for Type II diabetes and heart disease. You can be normal weight and yet still be at risk by packing fat in deep belly areas.

To be sure that children who were short for their age at adoption and then grew quickly are also heart and body composition healthy, we will be conducting a study using cutting-edge measures of body fat composition and cardiovascular health measures. Personalized results will be given to the parents of each participant and these can be taken to their pediatrician.

For this study we are looking for children and teenagers (ages 8 through 17 years) who were adopted internationally from orphanages or similar institutions.

In addition to personalized results, participants will be compensated for 1 visit to the University of Minnesota to have a full-body DXA scan of body composition, their cardiovascular health assessed, have blood drawn, and answer questionnaires.

If you would like more information about this study, please feel free to email Brie at reidx189@umn.edu