By Colleen Doyle

For the past three years, the Woman and Infants Study of Health, Emotions, and Stress (WISHES) has been collecting data to learn more about how women experience and cope with stress during pregnancy, and how stress might impact fetal and later infant development. To do this, we have enrolled 115 women and followed them and their developing children from early in pregnancy through the first few months of life. Enrollment was completed in January 2020, and we are currently working on finalizing data collection with active participants.

From a research perspective, prenatal stress is an umbrella term that can encompass many experiences that drive us “N.U.T.S.” in that they are Novel, Unpredictable, Threatening to our survival or our sense of self, and they foster a Sense of lacking control. This can include frustration with daily hassles, coping with uncertain or difficult life circumstances, and managing symptoms of anxiety or depression. Any pregnant woman can experience stress when she has more things coming at her than she can manage.

A growing body of research has linked different levels of prenatal stress experiences to both positive and negative outcomes for women and their developing children. The mechanisms that link women’s experiences during pregnancy to long-term child outcomes are complicated and not completely understood. However, recent research suggests that prenatal stress might influence child outcomes by impacting the in utero environment that helps shape brain development before birth. Some central research goals of the WISHES Study are to: (1) Understand what “prenatal stress” looks like across pregnancy when measured by self-report questionnaires and by levels of a stress hormone, cortisol, taken from collected samples of hair strands; (2) Examine the influence of prenatal stress on fetal development, as measured by fetal heart rate and fetal heart rate variability (FHR, FHRV) which are two well-established indices of central nervous system development; (3) Test whether cortisol levels are associated with self-report measures of stress, or whether cortisol levels may mediate or explain any associations between self-reported stress and differences in fetal development.

To help us address these goals, participants complete questionnaires on stress, emotions, and health behaviors 5 times during pregnancy and 1 time after pregnancy. At 3 time points during pregnancy and 1 time point following pregnancy, women also provide a small hair sample, which allows us to measure cortisol production during pregnancy. Cortisol is a hormone that helps our body cope and respond in challenging situations. During pregnancy, cortisol also helps mature fetal tissues, such as the lungs, and may impact the development of the central nervous system and brain. At 4 time points during pregnancy, women also complete fetal monitoring sessions, which involve placing electrodes on the woman’s belly to measure her baby’s resting heart rate with fetal electrocardiograph methods. We look at fetal heart rate because it is a “downstream” marker of fetal brain maturation; as central nervous system development unfolds during pregnancy the brain increasingly controls the heart, and in turn resting heart rate patterns show expected patterns of organization and change. Therefore, by measuring changes in resting fetal heart rate during pregnancy we are able to understand how prenatal experiences may play a role in setting up different trajectories of brain development.

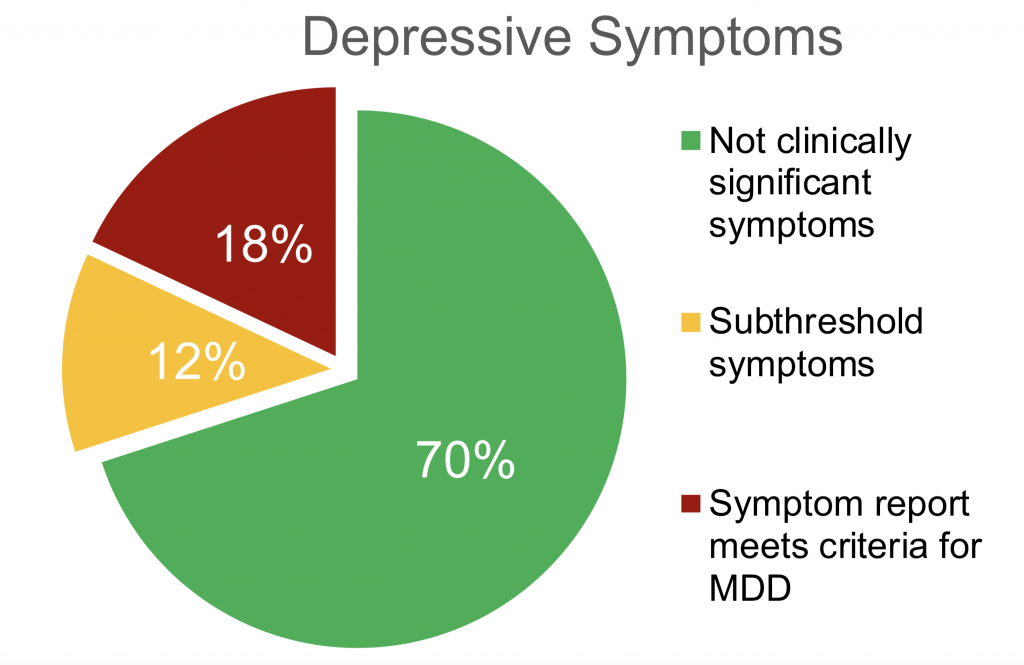

To date, 95 women and their children have completed all visits and we are nearing the end of data collection! As data collection is ongoing, we are not yet able to report on any significant findings. However, preliminary results continue to show that at enrollment, 18% of participants report clinically significant levels of depression or anxiety, meaning these levels of symptoms are impacting their day-to-day functioning and meet criteria for diagnosis and treatment of major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. This preliminary finding aligns with prevalence rates reported by previous studies examining these types of prenatal stress. Our preliminary results also continue to show an additional 12% of women are reporting “sub-threshold” levels of symptoms at enrollment, meaning they are reporting meaningful but more moderate levels of depression or anxiety and are not yet or currently meeting criteria for clinical diagnosis or intervention. Typically, OBs, midwives, and other health providers recommend these women be monitored closely as they are more likely to benefit from or need intervention and support at some point during pregnancy or the first year following birth. Finally, 70% of women report non-clinical levels of symptoms at enrollment, meaning this level is well under the threshold for either diagnosis/treatment or ongoing monitoring. Our next steps for analyses are to better understand the longitudinal course of self-reported symptoms and stress levels. For example, we want to know if women who report high levels of stress at the beginning of pregnancy are likely to remain stressed throughout pregnancy, or if these levels will decrease. Also, we will examine what characteristics may be associated with a woman reporting prolonged or increasing clinical levels of stress, versus women whose stress levels decrease or remain low, such as levels of social support, coping skills, personality traits, pregnancy symptoms (nausea, fatigue), and life events.

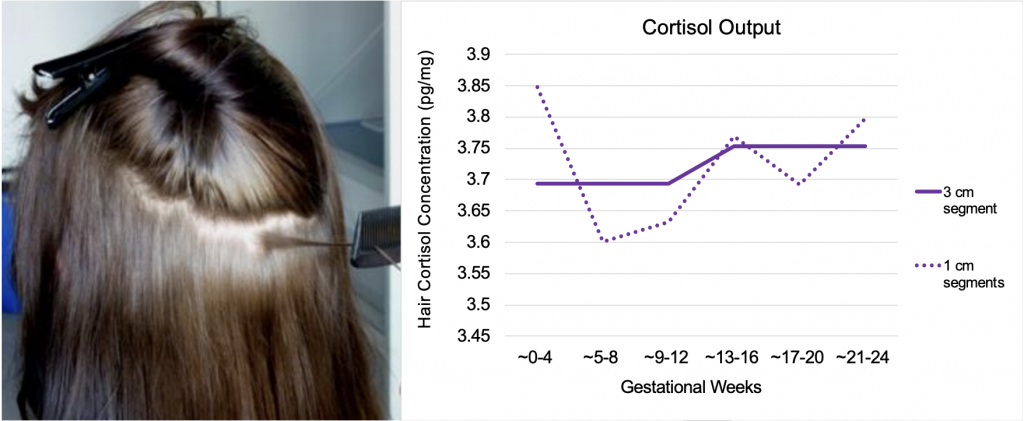

Additionally, we are seeing some interesting results from our hair cortisol samples suggesting that analyzing data at the level of 1 cm hair segments may yield important information about the variability in stress hormone output at different times during pregnancy. On average human hair grows approximately 1 cm a month, and our daily cortisol output is incorporated into hair strands as they grow. This means that the 1 cm of hair growth closest to the scalp represents a “stress calendar” of cumulative cortisol output over the last month. The use of hair samples to retrospectively create a calendar of cumulative stress hormone output is a relatively novel methodology for the field of developmental psychology. Currently, research shows that the 3 cm of hair growth closest to the scalp reliably reflects cortisol output over the past 3 months; hair growth beyond this 3 cm length is thought to inaccurately represent stress hormone production due to “washout” effects related to habitual hair care. For the WISHES study, we collect three hair samples at 3, 6, and 9 months of pregnancy and put together a retrospective stress calendar stretching across gestation. However, WISHES is one of the first studies to analyze hair cortisol concentrations from 1 cm segments instead of 3 cm segments. Typically this is not done due to cost of analysis per segment. Also, most research studies may not require data within a narrow, one month period. However, since development occurs at a rapid rate over pregnancy, for the WISHES study we are interested in examining cortisol output at a more precise increment of time. This will also allow us to better explore the possible association between cortisol levels and self-report levels of stress, which are also collected at one month time intervals. So far, our preliminary results show interesting differences in cortisol output when examined at a 1 cm/1 month time period versus averaging those values over 3 cm/3 month time periods, as seen in Figure 1. We hope that this means our study will be able to contribute new data on the typical trajectory of cortisol output during pregnancy, how it may be associated with self-reported stress, mood, or anxiety symptoms, and how it may be a potential way women’s experiences of prenatal stress at different time points during pregnancy may “get under fetal skin”.

Figure 1. Differences in hair cortisol when sampling 1 cm vs 3 cm during prenatal period.

We think our study has the potential to make important contributions to how parents, health care providers, and policy makers can help set up lifelong trajectories of health and well-being by supporting women’s mental and physical health during pregnancy. We are so grateful to all the women and families who have participated, as well as all the many research staff on the WISHES and Gunnar Lab team who have contributed to this project! We look forward to sharing more results next year!