By Carrie DePasquale

Children adopted from orphanages are at risk for something called Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder. That is, they are indiscriminate in who they approach, often being willing to go off with strangers and anyone who is “nice” to them. This pattern is seen among children still in institutional care and might be their way of getting their needs for affiliation met, even by people they have never seen before. In previous newsletters, we have reported that for most orphanage-adopted children, this behavior wanes over time. However, for some, it doesn’t go away and even increases.

Parents who adopted children from institutions worry about this behavior. They get lots of advice on what to do to reduce it. As part of the Transition into the Family Study that we completed in 2015, we observed and coded parent-child behavior four times over the first two years the child was in the family. We had parent and child play together, perform a difficult task together and then clean up toys. We also conducted assessments of how the children reacted to a stranger who tried to play with them.

Parenting that demonstrates responding adaptively to children’s needs and setting clear rules and limits may help children hone their attention skills and thus help with sorting who they should and should not cuddle up to.

In a recent analysis, we asked which dimensions of parenting were important for curbing disinhibited social approach. Developmental psychologists typically examine two dimensions of parenting: (1) how sensitive and responsive is the parent and (2) how skillfully and patiently does the parent impose limits and provide structure and guidance. The first dimension, sensitivity and responsiveness, examines the parent’s attempt to follow the child’s lead and respond when needed, but not intrusively when not needed. The second dimension examines the parent’s ability to set limits (“It is time to clean up now”) and provide structure (“in a few minutes we are going to clean up, so finish up what you are doing”). In a sense, the first dimension allows the child to be in the driver’s seat, while the second allows the parents to set the rules of the road.

It is important to note that nearly all of the parents in the Transition into the Family Study scored average to really high on both of these dimensions, especially on the sensitivity and responsiveness. Nonetheless, we did find that parenting helped explain some of the variation in disinhibited social approach, especially the more extreme aspect of it, which was making physical contact with the stranger (i.e., climbing in her lap, leaning up against her).

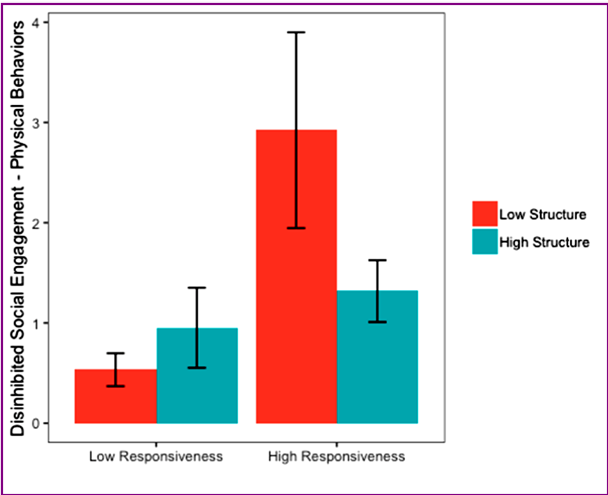

Figure 1 shows that being highly responsive seems to be a risk factor for the children continuing to show high levels of disinhibited behavior, unless it was accompanied by high levels of structure and limit setting. Generally speaking, developmental psychologist think that being high on both dimensions of parenting is a good idea. However, here we see that if we are going to put our kids in the driver’s seat and these kids come from institutions and are at risk for atypical social behavior, we had better also hone our skills at setting limits and providing lots of structure.

Why? We are not sure. It could be that lots of “following the child’s lead” (a.k.a. sensitivity and responsiveness), led these parents to inadvertently reward their children for being friendly to strangers. After all, if this is what the child seemed to want to do, then the sensitive parents will go with that. Alternatively, it might be that the key to helping children who started out in institutions to figure out what and who they need to pay attention to is really clear “rules of the road” that are imposed carefully, logically, and consistently. In earlier work, we found that children who continued to show lots of disinhibited social approach behavior were also children who struggled with regulating their attention. Parenting that demonstrates responding adaptively to children’s needs and setting clear rules and limits may help children hone their attention skills and thus help with sorting who they should and should not cuddle up to.

As in any good study, one finding leads to many questions. For now, though, it is pretty clear that children who are adopted from orphanages benefit from parents who both “follow their lead” and gently, clearly, consistently, and calmly “set the rules for the road”.

*Parenting note: If you are now remembering every time that you “caved in” to a child’s demand after setting a limit, please know that you are a normal parent. Remember we were scoring parents while they were in the laboratory knowing that we were watching what they and their child were doing.