By Danruo Zhong

A previous study (Reid et al., 2017) from our group found that children who spent their early life in institutional care (e.g., orphanages) have a higher risk of growth stunting at the time of adoption. But the good news is that once they were placed with warm and well-resourced families, most children rapidly caught up to normal height and weight, although they remained shorter and thinner than children born and reared in Minnesota for at least several years after adoption.

Puberty, however, brings another rapid period of growth. In an early study of children adopted from Romania into England, at puberty previously institutionalized youth grew less than other youth and thus ended up even shorter relative to others by the end of the pubertal growth spurt.

We wondered whether this would be true of children adopted from less dire circumstances than those children who first came out of Romanian institutions in the 1990s. Stress slows growth quite literally. Stress hormones reduce the production and power of the growth hormone system. This is probably because when you are experiencing stress and threat it is not the time to put energy into growth. Thus we wondered whether youth who were experiencing more stress might show less of a pubertal growth spurt.

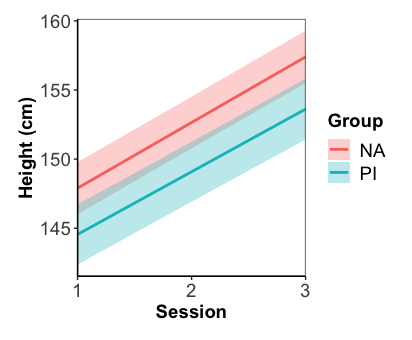

To answer these questions, we examined data from a study we conducted on puberty and its relations to children’s functioning. In this study, we had children who were 7 to 14 years at the beginning of the study and then we assessed them at yearly intervals for several years. Each time we saw them we assessed their pubertal development and their height, weight and weight-for-height or body mass index (BMI). Roughly half of the children had been adopted internationally from institutional care and half were born and raised in their birth families here in Minnesota. We did not find any group differences in linear (height) growth, as seen in Figure 1. Previously institutionalized (PI) youth were shorter at the beginning of the study and they remained shorter but growing at the same rate as comparison non-adopted (NA) youth. Stress was not related to linear growth for either group.

All of the statistically significant differences were in BMI. At visit one, the previously institutionalized (PI) youth were thinner than the comparison non-adopted (NA) youth (see Figure 2), but over this pubertal period their BMIs increased more rapidly. By the third visit, two years after, there was no significant difference between the groups. What this may mean is that if this continues into adulthood, a history of early institutional care may put the person at risk for being overweight. To know this, though, we will need to conduct a study of adults who were adopted from institutional care as infants and young children.

As for stress during the pubertal period, here we found that it was associated with more rapid increases in BMI for both groups of youth. This last finding is rather striking because, for the most part, the youth in this study were not experiencing high levels of stress. Yet even in this range, stress was associated with increasing BMI.