By Keira Leneman

While we all may experience varying degrees of struggle in getting out of bed and starting the day, our body helps do some of the work for us. Shortly before our eyes open and in the minutes following, a stress hormone called cortisol influences this routine process. The body releases cortisol in response to stressful events, but also regularly throughout the day in a circadian rhythm cycle. Levels are highest early in the morning and then drop throughout the day to the lowest levels in the first half of the night. The cortisol awakening response (CAR) is superimposed on top of the day-night rhythm of cortisol. It consists of a spike in cortisol levels within the first 30-45 minutes after awakening and is considered by some to be a type of preparation for the day, like a cup of coffee. Using saliva samples collected by families in their homes, we are able to gather information about how stress systems might function differently on an everyday basis in children who spent some of their early months living in orphanages before being adopted compared to children born into their Minnesota families.

A few years ago our research group examined children at the transition to adolescence and found that early in puberty, children adopted from orphanages had more blunted CARs (less pronounced rise in the morning) than non-adopted children. However, when older and farther along in puberty, the adolescents adopted at a younger age had CAR patterns similar to the non-adopted group—they were no longer blunted. This data suggested that puberty might provide a period for recalibration of physiological stress systems, especially when early life adversity was experienced for only a short period of time.

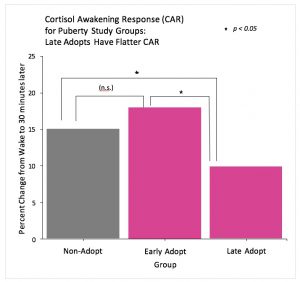

In the Puberty Study, we again collected saliva samples in the time right after waking up. We have only looked at the data from the first year of our study, but are seeing some hints at similar patterns. We have found that as children progress in puberty they show larger “spikes” in cortisol when they wake up. We then examined whether spending your early life in an orphanage affected this cortisol response to awakening. As we had seen before in previous studies, Figure 3 shows that children adopted later (16 months or older) had a smaller spike in cortisol after awakening than children adopted earlier in life (before 16 months) or those born into their families in Minnesota.

So far we have not seen a cortisol awakening response change with puberty, but it is still a possibility as the children in this study get older and are more advanced in pubertal development. As we begin to analyze data from year 2 and year 3, we will be able to look at a wider range of pubertal status to get a better sense whether these patterns are changing throughout this developmental period. Year 2 is almost complete, so we should be able to begin the next level of these analyses shortly.