By Colleen Doyle and Erica Smolinski

What is the goal of the WISHES study?

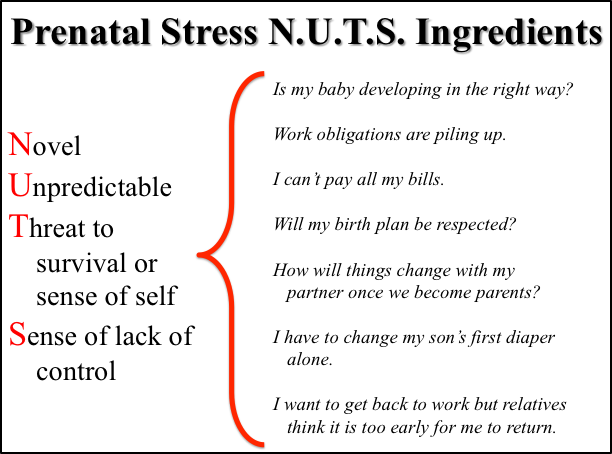

No pregnancy is stress free, although prenatal stress can manifest in different ways for different women. From a research perspective, prenatal stress is a complex umbrella term that encompasses many experiences, including frustration with daily hassles, symptoms of anxiety or depression, and life circumstances such as financial concerns, the death of a loved one, or a disaster like flooding. Overall, prenatal stress includes experiences that drive us “N.U.T.S.”, in that these things are Novel, Unpredictable, Threatening to our survival or our sense of self, and they foster a Sense of lacking control. This acronym isn’t meant to make light of prenatal stress, but rather to help us remember that prenatal stress occurs when a woman has more things coming at her than she can manage.

No pregnancy is stress free, although prenatal stress can manifest in different ways for different women. From a research perspective, prenatal stress is a complex umbrella term that encompasses many experiences, including frustration with daily hassles, symptoms of anxiety or depression, and life circumstances such as financial concerns, the death of a loved one, or a disaster like flooding. Overall, prenatal stress includes experiences that drive us “N.U.T.S.”, in that these things are Novel, Unpredictable, Threatening to our survival or our sense of self, and they foster a Sense of lacking control. This acronym isn’t meant to make light of prenatal stress, but rather to help us remember that prenatal stress occurs when a woman has more things coming at her than she can manage.

A growing body of research has linked different levels of these different types of “prenatal stress” experiences to both positive and negative outcomes for women and their developing children. For example, mild levels of prenatal stress have been linked to enhanced motor and cognitive development in infancy. In contrast, more intense or chronic experiences of prenatal stress have been associated with increased risk for an earlier birth, as well as problems with learning and controlling emotions during childhood.

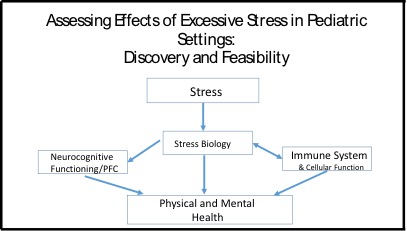

The mechanisms that link women’s experiences during pregnancy to long-term child outcomes are complicated and not completely understood. However, recent research suggests that prenatal stress might influence child outcomes by impacting brain development before birth. The goal of the WISHES study is to increase our understanding in this area. We hope to learn more about how women cope with stress during pregnancy, and how their experiences during pregnancy may “get under the skin” of their developing children to influence their brain development, behavior, and health. We think our study has the potential to make important contributions to how parents, pediatricians, and policy makers can help set up lifelong trajectories of health and well-being by supporting women’s mental and physical health during pregnancy.

What’s involved in participating in the WISHES study?

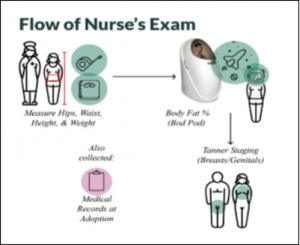

To study the question of how prenatal stress may influence the health and development of women and their children, the WISHES study is following women and their children from early in pregnancy through the first few months of life. Women enroll in the study between 8-16 weeks of pregnancy, and complete questionnaires on stress, emotions, and health behaviors 5 times during pregnancy and 1 time after pregnancy. At 4 time points during pregnancy, women also complete fetal monitoring sessions, which involve placing electrodes on the woman’s belly to measure her baby’s resting heart rate.

We look at fetal heart rate because it is a “downstream” marker of fetal brain maturation; as central nervous system development unfolds during pregnancy the brain increasingly controls the heart, and in turn resting heart rate patterns show expected patterns of organization and change. Therefore, by measuring changes in resting fetal heart rate during pregnancy we are able to understand how prenatal experiences may play a role in setting up different trajectories of brain development.

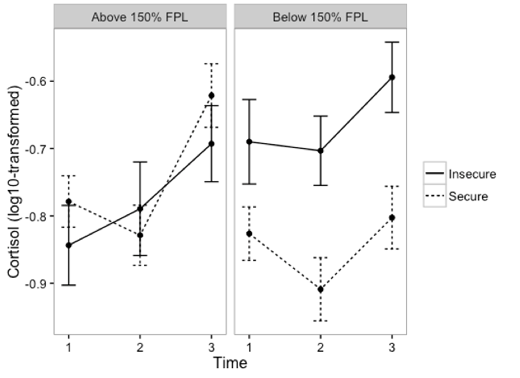

At 3 time points during pregnancy and 1 time point following pregnancy, women also provide a small hair sample, which allows us to measure cortisol production during pregnancy. Cortisol is a hormone that helps our body cope and respond in challenging situations. During pregnancy, cortisol also helps mature fetal tissues, such as the lungs, and may impact the development of the central nervous system and brain. Finally, at 2 time points women complete a short computer game while we track their eye-movements, in order to understand how differences in attentional styles may play a role in whether or how women experience stress during pregnancy.

Study enrollment and data collection

So far, 81 pregnant women have enrolled in the WISHES study. Recruitment is ongoing, and our goal is to include up to 120 women. To date, 32 women and their children have completed all visits. As data collection is also ongoing, at this time we are not yet able to report on any significant findings. However, preliminary results suggest that approximately 15-20% of participants report clinically significant levels (i.e., levels that impact their day-to-day functioning) of depression or anxiety at one or more pre- or postnatal study visits. This aligns with prevalence rates of previous studies examining prenatal stress. For us, it also underscores an important point that is often overlooked in this area of research – prenatal stress is not exclusive to the prenatal period. This is important because it means that researchers, health care providers, and policy makers – not to mention partners, family members, and friends – have many opportunities during pregnancy and after delivery to help and support women and their children.

Join us for the WISHES study!

Every day we are learning more about how experiences during pregnancy may play a role in a child’s growth and development. However, we have much more to learn. This WISHES study will be the first to connect the dots between prenatal experiences, brain development across pregnancy, and brain and behavioral development during the first two years of life. This will allow us to significantly advance our understanding of how prenatal experiences may play a role in setting up different trajectories of brain and behavioral development.

Women and families can be compensated up to $210 for participating. For many of the prenatal visits we are able to meet with women at their homes. For all visits held at the U of M, we provide free parking and child care for older siblings. For more information on the study please email us at wishes.umn@gmail.com.

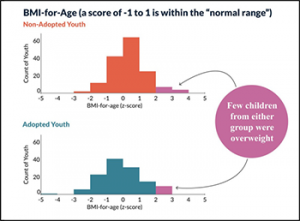

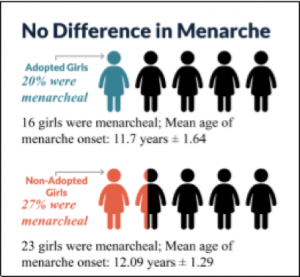

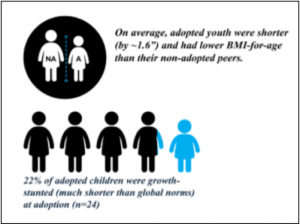

Throughout evolution, humans have experienced periods of feast and famine. Growing evidence suggests that adversity and height growth stunting early in childhood increases risk for early onset puberty (in girls), obesity, and poorer mental health later in life. Researchers think that this is the case because in the first 1,000 days after conception, our very young, growing bodies determine whether the environment we are growing up in has a lot of resources or has little resources. In this way, our bodies “calibrate” to the environment we expect to grow up in. However, researchers think that early physical adaptations to harsh environments with very little resources may increase later risks of obesity, early onset puberty in girls and metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, because our bodies do not anticipate a shift from resource-poor to resource-rich environments.

Throughout evolution, humans have experienced periods of feast and famine. Growing evidence suggests that adversity and height growth stunting early in childhood increases risk for early onset puberty (in girls), obesity, and poorer mental health later in life. Researchers think that this is the case because in the first 1,000 days after conception, our very young, growing bodies determine whether the environment we are growing up in has a lot of resources or has little resources. In this way, our bodies “calibrate” to the environment we expect to grow up in. However, researchers think that early physical adaptations to harsh environments with very little resources may increase later risks of obesity, early onset puberty in girls and metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, because our bodies do not anticipate a shift from resource-poor to resource-rich environments.