By Brie Reid

Inside our bodies and on our skin, trillions of microorganisms from thousands of different species coexist together and help our human body function. We call all these microorganisms the “microbiome.”

“Picture a bustling city on a weekday morning, the sidewalks flooded with people rushing to get to work or to appointments. Now imagine this at a microscopic level and you have an idea of what the microbiome looks like inside our bodies, consisting of trillions of microorganisms (also called microbiota or microbes) of thousands of different species.”

– (Quote from Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health)

Each person has their own unique microbiome: it develops over time as we grow up and experience the world around us. Our microbiome is influenced by environmental and genetic factors. As we grow, what we eat and environmental exposures can change our microbiome’s composition. This change can either be good for our health or could increase our risk for disease. The microbiome, especially the gut microbiome, is important to immune system development and the communication between our brain, our immune system, and our microbiome during development may influence our mental and physical health later in life.

Understanding the role of the gut microbiome in health and disease is at the forefront of neuroscience and psychiatry research. In this study, we examined the diversity and composition of the gut microbiome using in fecal samples from adolescents adopted internationally as infants and toddlers into the United States from institutions (orphanages) and adolescents reared in their birth families in the United States. We found that exposure to early life adversity resulted in microbiota-immune changes that persisted into adolescence.

We found compositional differences in the amount of type of microbes in the guts of adolescents adopted from institutions and those born and raised in Minnesota all their lives. Everyone had the same type of microbes, but they differ in how many of each they had. This is called Beta diversity.

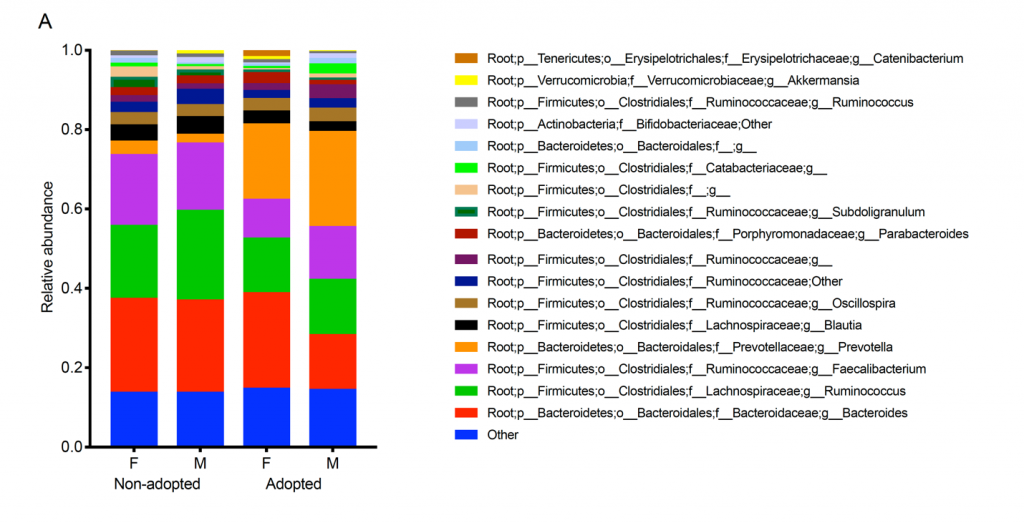

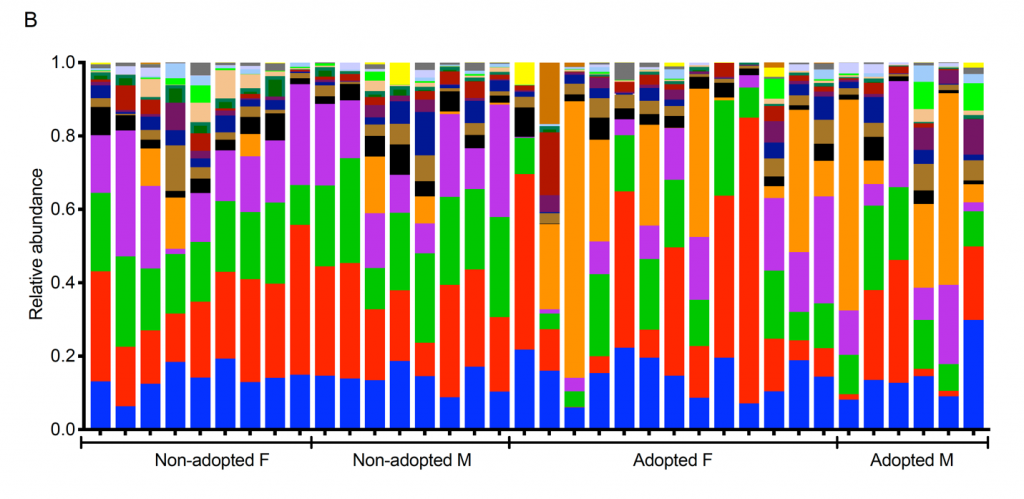

You can see these compositional differences (beta diversity) in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Figure 1 shows the compositional differences of the microbiome in each group of adolescents, and is broken down by sex. In Figure 2, every column of colors represents one person’s microbiome. We look at compositional differences by comparing the taxa (types of microbes) represented between individuals and groups through the blocks of color in the columns. For example, notice how there is a greater abundance of Prevotella in the adopted adolescents compared to the non-adopted adolescents (shown in orange). Prevotella is an abundant bacterial taxa that has been previously associated with diet but also with infection. We also found that several bacterial taxa including Bacteroides and Coprococcus were also higher in adopted youth.

Three things are noteworthy. First, your gut microbiome reflects what you eat. Since these adolescents were adopted as infants and toddlers, they were eating diets similar to the non-adopted comparison adolescents. Yet, their microbiota look different from our comparison adolescents. This suggests that, as found in animal studies, there might be an early period when the basic pattern of our gut microbiome gets established. Second, the adolescents in this study came from many different countries and probably did not have the same early diet. So, it is likely something other than diet shaped their gut microbial diversity patterns. The particular taxa (types of microbes) that are more prevalent in the adopted adolescents are associated with stress. Thus, it is possible that stress is what is similar across the adopted youth. Even though they come from different countries, the stresses associated with being raised in an institution may be what is contributing to similarities in adopted youth’s microbiome. Third, Figure 1 is the average. In Figure 2, you can see each individual and it is pretty clear that the average is a fairly good reflection of most of the participants, even though the adopted adolescents came from different countries and parts of the world.

Last year we told you that when we studied these adolescents, plus a number more who were part of our Immune Study, we found that their immune systems also revealed a signature of their early experiences. Notably, their T-cells, which are the part of the immune system that searches out and destroys invaders, were more likely than those of non-adopted youth to be tagged with a protein called CD57. This protein gets attached to T-cells that have done a good deal of “battle” and are beginning to get “too old to fight” (T-cells go through a life cycle like we do). This doesn’t mean that the adopted youth could not fight off infections, but rather that their T-cells told a story of having had to fight more when they were younger than the T-cells of the non-adopted youth. This makes sense because institutions are places where children are exposed to many pathogens. Indeed, nearly all of the adopted youth carried evidence of exposure to one common pathogen, CMV (which causes cold sores), while only a few of the non-adopted youth did.

Animal studies show that the gut microbiome helps shape the immune system. So we were interested in whether our T-cell findings were related to our microbiome results. We found that they were. The ratio of T-cells tagged with CD57 protein was associated with a certain elements of the gut microbiome. One of the associations was with a bacteria, Alistipes. This is interesting because Alistipes has been suggested to play a role in microbe-immune interactions that influence risk of stress-related outcomes.

What does all this mean? First, it means we need to do more research to check that our findings are solid. There were only a few participants in this microbiome study because it was what we call a pilot study. A pilot study is a small study where we see if there is something there to study in the first place. Now we need to do a larger study, and for that we will need to write a grant. Second, no one yet really knows what the health implications are of different patterns of microbes in your gut. More than likely the pattern we see in the adopted youth has its minuses and pluses. Third, it reinforces all of the findings we are obtaining that say that the first year or so of a child’s life matters. At the same time, we need to remember that in many ways, the youth in our studies who were adopted from orphanages and other institutions are doing remarkably well. Thus early matters, but so does later.