By Brie Reid

Inflammation is a key part of our immune system: when our body experiences inflammation in the short-term, it helps our wounds heal and our body recover from some illnesses. Chronic, low-level inflammation is different, as it reflects the body’s inability to return to a non-inflamed state. Chronic, low-level inflammation seems to play a role in a lot of different diseases such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, cancer and, in some cases, depression. The theory is that adverse early care environments are believed to negatively impact the immune system and contribute to a pro-inflammatory state that is thought to increase risk of chronic, low-level inflammation as the individual ages. Youth who are currently living in harsh psychosocial conditions have been noted to show chronic increases in inflammation. However, it is difficult to know if the inflammation in individuals who have experienced adverse early care environments are due to the early care environments themselves, or due to continued and significant life stressors throughout childhood and adolescence. This is because most individuals experiencing adverse care in infancy go on to experience significant life stressors throughout childhood, making it difficult to isolate the impact of the infancy period. This is not the case for children adopted internationally from orphanages and other institutions. For them, harsh conditions end with adoption. We wanted to know if, under these circumstances, we would see a pro-inflammatory state in teenagers adopted from orphanages versus teens who were not adopted, but reared in families similar to those of the adopted teens.

The good news is that we found no evidence of chronic, low-grade inflammation in the adopted teens. When we examined their plasma, their levels of several indices of inflammation were no higher than those of the comparison teens and for both groups levels were in the normal range. To probe more deeply, we put the white blood cells in culture and stimulated them with different pro-inflammatory challenges. On two of these challenges we saw no significant differences between the cells from the adopted and the comparison teens. More good news. However, on one of the challenges the cells from the adopted teens responded more. Thus, there may be some slight bias towards greater inflammation, but at least as adolescents, it is not pronounced.

One reason we may not be seeing a pro-inflammatory state in the youth adopted out of harsh early life conditions is that this state is highly associated with obesity and being overweight. Many youth growing up in poverty and chronic stress are also overweight. However, youth adopted from orphanages, as a group, are not. We found the expected association between body mass and chronic inflammation in both the adopted and comparison group, though on average the kids in both groups had healthy weight for their heights.

Orphanages are often breeding grounds for parasites and other viruses and pathogens. Many children adopted from these institutions have been exposed to high pathogen loads, relative to kids born into highly resourced homes in Minnesota. This means that their immune system had to work hard early in life. For many of these kids they harbor forms of the herpes virus that their immune system has to chronically fight to keep the virus in check. One such virus is the cytomegalo virus of CMV. By the time most people are old (e.g., 60 years or more) they have acquired this virus and are keeping it in check. Thus the virus is nothing to worry about. Acquiring it early, however, means that your immune system has had to work to check it for many more years. This may speed up the aging of the immune system relative to individuals who acquire these viruses later in life.

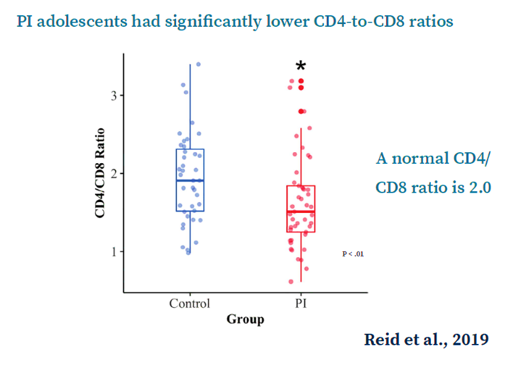

In the Immune Study we found that most of the adopted teens had the CMV virus and were keeping it in check, while less than half of the comparison teens tested positive for CMV. We then examined two types of T cells, CD4 and CD8. Simplified, the CD4/CD8 ratio is a reflection of immune system health and a normal CD4/CD8 ratio is between 1 and 4. In much older populations, a ratio below 1 is indicative of immune insufficiency. In our study, neither adopted or comparison teens had a CD4/CD8ratio below 1, but the teens adopted from orphanages had a lower ratio than their non-adopted peers. Figure 1 depicts what are called box and whisker plots. Each dot is a teen in our study. The line in the middle of each box is the average or mean, the top and bottom of the box are the 25th and 75th percentile and the whiskers indicate the highest and lowest score. Of concern, we did see some of our adopted teens scoring below one. There is very little normative data on healthy teenagers and all of the teens in this study were healthy. Thus it is not clear what a score below one would mean at this age. It might mean nothing, it might mean that a susceptibility to having a harder time fighting viruses and such. We do, however, have an idea why some of the adopted teens were scoring so low. They were the ones who had higher CMV levels.

Because chronically keeping CMV in check from early in life may age the immune system, we also examined T cells for the presence of a protein call CD57. T cells go through a life cycle. When they are first birthed from the thymus gland they are naïve. Then they encounter a pathogen and start differentiating and maturing. At the last stage they become terminally differentiated and acquire this CD57 protein. Older people may have many terminally-differentiated T cells that are tagged with CD57, a sign of an aged immune system. One way to think of this is like the young T-cells are flexible warrior or soldiers who are ready to learn to fight many types of invaders. But with each battle they fight they begin to get set in their ways. They become like generals with many medals who are good at fighting the old wars, but become less and less able to fight the new ones.

There’s evidence of immune differences (in T-cell profiles) in post-institutionalized adolescents, which is suggestive of accelerated immune aging or immune senescence.

What we found in the Immune Study was that the adopted teens had more terminally-differentiated CD4 and CD8 T cells that were tagged with CD57. These were far from the majority of their cells, but they had more of them than the comparison teens. The percentage of CD8+ CD57+ cells was predicted by the level of CMV in the blood. Thus, like the ratio of CD4 to CD8, chronically battling this virus since infancy seems to have produced a more mature, more experienced, and thus a slightly more aged immune system.

We can only speculate that had these teens not been adopted, had they remained in institutional care, we would have found even more evidence of immune aging and perhaps more evidence of chronic inflammation. Adoption likely halted the assault on the immune system, but still left a signature of what the immune system had to deal with when these teens were very young.