CEED is delighted to welcome Anne Larson, PhD, to our team as a research associate. Dr. Larson studies the development and implementation of practitioner-supported and caregiver-implemented language assessments and interventions for young children. She and her family have just relocated to the Twin Cities from Utah, where Dr. Larson was on the faculty at Utah State University. However, she is no stranger to Minnesota, having completed her doctorate at the University of Minnesota after establishing a career as a speech-language pathologist in Twin Cities public schools.

Q: Your research centers on language assessments and interventions for young children. Talk a little bit about some of the specific topics that interest you.

AL: In terms of language assessments, I’m interested in identifying screening and progress monitoring tools that can be used for children under age three. There are very few measures available and even fewer that have included children and families from historically marginalized racial, ethnic, and linguistic groups in their development. In a recent project, we looked at the initial validation of the Early Communication Indicator (ECI) for Spanish- and Spanish-English dual language learners. Long-term, I’d like to explore modifications of the ECI and other measures, such as vocabulary checklists, for children from a variety of cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

My research on language interventions typically involves children who are around 18-30 months old. However, the projects I work on actually focus on the adult caregiver or caregivers who interact with the child. For one recent study, we trained early intervention providers to use a coaching approach in their work with caregivers of young children with disabilities. Although the focus of the study was changing provider behavior, the ultimate goal was to promote the use of naturalistic language intervention strategies by caregivers. Using these strategies, the caregivers can then affect child language outcomes.

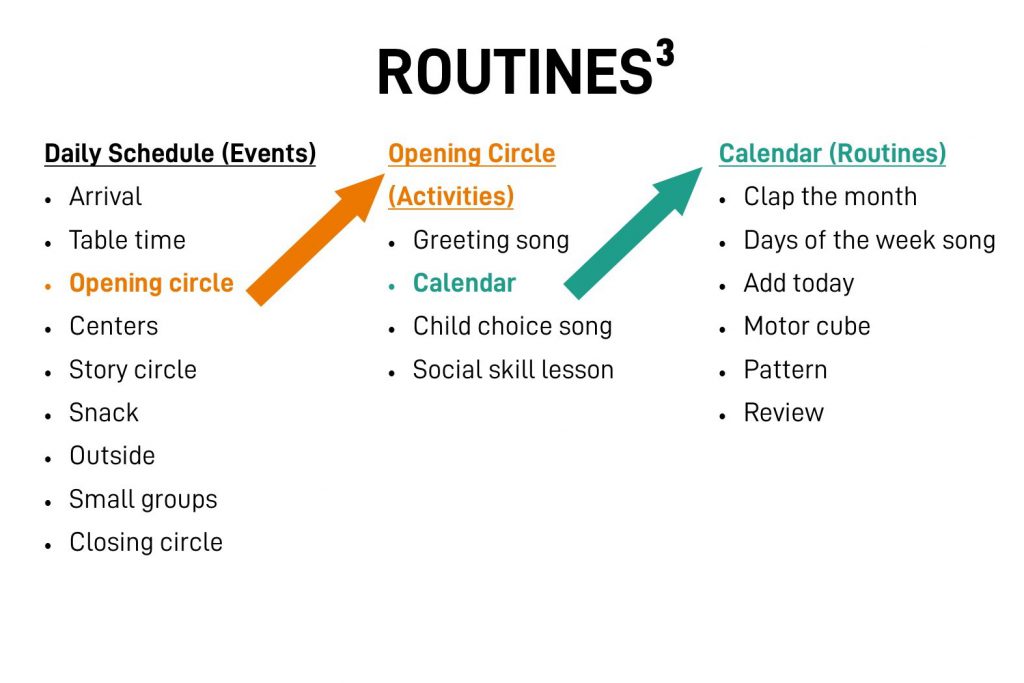

Naturalistic language interventions are ways to support responsive and engaging interactions between children and their caregivers. Caregivers can include parents, other family members, childcare providers, and so on. An example of a naturalistic intervention strategy might be: “Comment on what the child is doing.” This strategy encourages caregivers to provide more language input around their children. These strategies are designed to be embedded within everyday activities and routines, rather than adding something extra for caregivers to make time for with their children.

Q: Your work is described as community-based research. Could you talk a bit about what that term means, as well as the rewards and challenges of this type of research? Why is this approach so important?

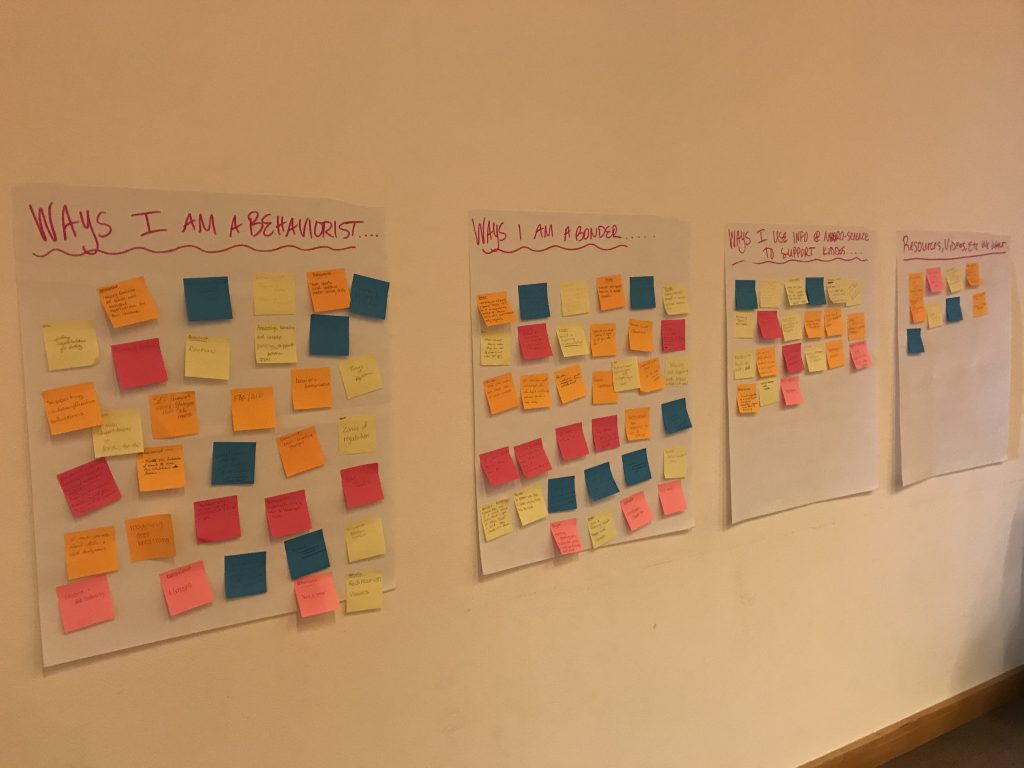

AL: I think of community-based research as having a genuine interest in community needs and making a concerted effort to work with community members and stakeholders as part of the research team. This approach is very rewarding to me, because I know that my research is immediately relevant to the target group. It is sometimes challenging, however, to describe this more collaborative approach, because some communities have had the experience of researchers coming in and telling them what to do without first engaging them and listening to their needs. I’m looking forward to building on relationships I have in Minnesota, understanding community needs, and continuing with this work to make critical strides for young children and families in Minnesota.

Q: Tell us about the work you will be doing with your Institute of Educational Sciences Career Award.

AL: The Early Career Award is focused on designing a language intervention that I refer to as VALI (Video- and App-based Language Instruction). This will be a four-year project. We’ll develop three iterations of an intervention for Spanish-speaking families who identify as Latinx and also have young children with language delays. Caregivers will access an app with information about naturalistic language intervention strategies that they can use with their children. Caregivers will also participate in back-and-forth asynchronous coaching with a trained bilingual early interventionist who can support their individual family needs.

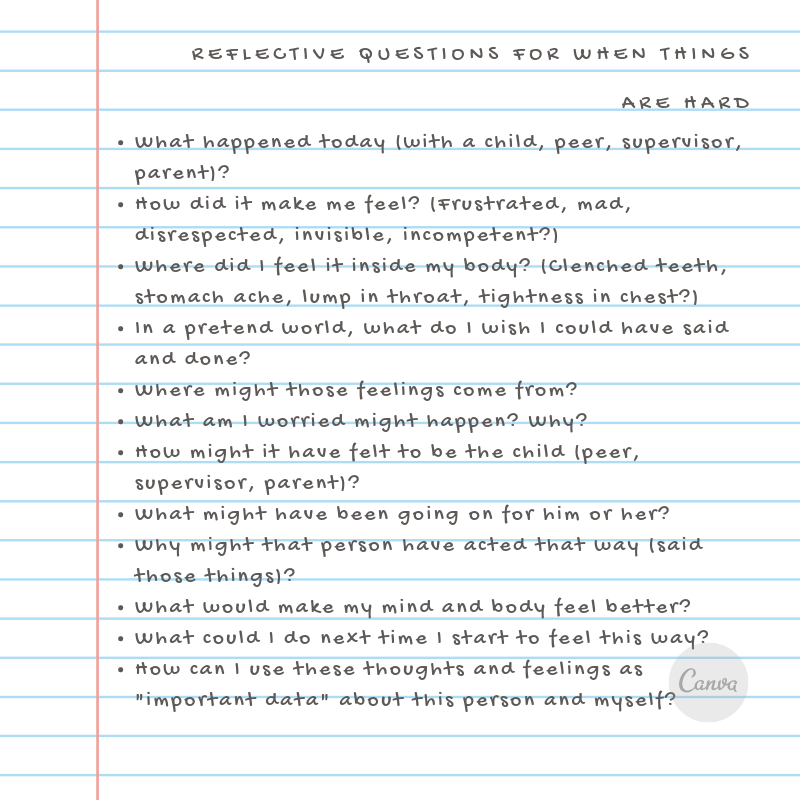

Q: Your role at CEED will also include work with the Reflective Practice Center; how does reflective practice come into play in your area of study?

AL: Reflective practice has a lot of similarities with the coaching-based models I use in my research. The more I learn about reflective practice, though, the more ideas I encounter that can be incorporated into my work. I’m looking forward to expanding reflective knowledge and practice within the field of early intervention. I think there are many practitioners who, like me, may not previously have been aware of reflective practice or its benefits for providers, families, and children alike.

Q: What are some of your interests and hobbies outside of work? (That’s assuming that family life with young children allows for hobbies!)

AL: You’re right that “me” time is fairly limited with two young children! I enjoy family bike rides, hiking, and camping.