The Tri-Psychology Programs – Educational Psychology, Psychology, and the Institute of Child Development (ICD) – at the University of Minnesota are pleased to announce the recipients of the 2023 Tri-Psych Graduate Student Diversity Fund grants. The goal of these awards is to build community and facilitate cross-departmental collaborations among Tri-Psych graduate students of color and/or student groups otherwise underrepresented in postsecondary education.

Congratulations to this year’s recipients!

Vanessa Wun and Andrea Wiglesworth (Psychology), Sarah Pan and Jasmine Banegas (ICD), Mahasweta Bose and Thuy Nguyen (Educational Psychology)

This project addresses a critical need for first-year PhD student mentorship by pairing first-year students from historically underrepresented backgrounds in psychology with experienced students within their program also from underrepresented backgrounds. This work builds on the unfunded graduate mentor program currently in ICD, as well as the Next-Gen Psych Scholars Program (NPSP). Importantly, it continues our efforts initiated through this funding platform in 2022, through which we founded the Diversity in Psychology Support (DIPS) mentorship program. DIPS aims to continue to increase a sense of belongingness and self-efficacy while also reducing imposter syndrome for incoming cohorts by pairing individuals with a more senior student who can provide support, answer questions, and encourage the mentee in their degree progress during the first year. Ideally, these mentorship relationships would last beyond the first year, and provide longer-term support for students throughout the program duration. These goals support our ultimate objective of retention of underrepresented students in graduate school.

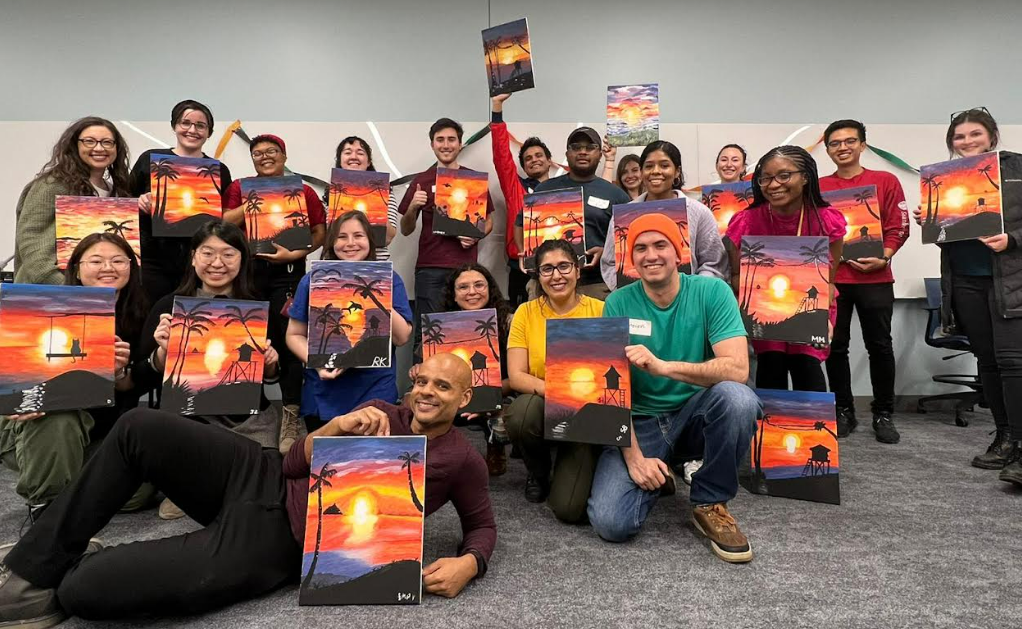

Mirinda Morency and Norwood Glaspie (ICD), Jessica Arend (Psychology)

Paint Nite has emerged across the country as a creative way to bond with friends. Everyone in the class works towards creating their own version of the same painting while learning how to mix colors, apply paint on canvas, and create compositions. Last spring, ICD first years hosted a successful paint nite social, and attendees still talk today about their positive experience. Marginalized, underrepresented students are more likely to feel like they don’t belong at universities. Social belonging is key to success, so hosting events like Paint Nite can help address this issue. This also promotes Tri-Psych diversity initiatives in that it fosters a welcoming, affirming, and inclusive space to talk, spend time together, and participate in creating something unique. Doctoral programs in R1 universities are demanding, and so creative social events can also combat feelings of disconnection and burnout. The aims of this event are two-fold: (a) promote creativity, inclusivity and community, and (b) serve to sustain mental wellness and release stress.

Shujianing Li (Psychology), Thuy Nguyen (School Psychology), Romulus Castelo (ICD)

The COVID-19 pandemic has had negative sociopolitical, financial, and psychological consequences. As the general population experiences increased vulnerability to burnout, Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) students face additional distress from growing anti-AAPI racism. Moreover, conversations on mental health and racism are not normalized within the AAPI community, creating barriers for those needing psychological services and resources. To tackle these challenges, we will create a burnout prevention toolkit for AAPI undergraduate and graduate students. With the proposed toolkit, AAPI students will: 1) self-identify burnout, 2) discover grounding techniques and resources for immediate support, and 3) explore culturally informed practices that promote long-term psychological health. We will consult academic (e.g., peer-reviewed articles) and non-academic (e.g., advice from community advocates for other advocates) sources to inform the toolkit’s burnout prevention content. The final product is a wallet-size card deck, usable in electronic and physical forms. The toolkit will provide accessible and broadly applicable psychoeducation and actionable suggestions. While the toolkit could be beneficial for AAPI students in other departments, we will prioritize disseminating it to undergraduate and graduate students in the ICD, the Educational Psychology Department, and the Psychology Department.

Jessica Arend, Caroline Ostrand, Marvin Yan, Adrienne Manbeck, and Kate Carosella (Psychology); Mirinda Morency (ICD); Shayna Williams and Elizabeth Shaver (Educational Psychology)

We will deliver a three-part series on disability and inclusive access: 1) A guest speaker address on supporting students with disabilities and promoting accessibility in academia; 2) An affinity group discussion for self-identified graduate students with disabilities, chronic illnesses, and neurodiversity. This meeting will provide space for students with shared experiences to reflect on the address together; and 3) A discussion open to all students, faculty, and staff, promoting education and informed action. Informed by the address, we will discuss ways to promote accessibility and equity for disabled-, chronically ill-, and neurodiverse-identifying students. All meetings will be in hybrid format, allowing for accessible remote or in-person participation. From these events, two student “editors” will compile a comprehensive list of resources on disability and accessibility for students and instructors/mentors. We will establish this series as a yearly tradition, and we will recruit a focus group of 10-15 students who self-identify as having disabilities, chronic illness, or neurodiversity to provide feedback about events and future areas of advocacy.