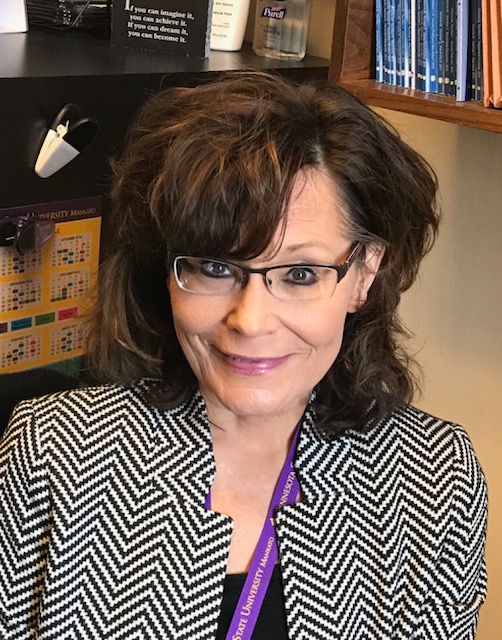

ICI alum Teri Wallace dropped by the Institute recently to help celebrate the 35th anniversary of Impact magazine.

“It felt like being home,” said Wallace, now the interim associate vice president for research and dean of the extended campus at Minnesota State University, Mankato. “I spent my years with ICI in Pattee Hall, so the structure is of course very different, but the people and the feeling were the same, and I only wish I had more time to sit and reconnect with colleagues.”

Wallace worked at ICI from its earliest days in the late 1980s until 2010, when she left for Mankato to serve as a professor of special education. Starting as a graduate research assistant at ICI, she held a variety of positions, including principal investigator and assistant director.

Today, she’s working on improving Minnesota State Mankato’s transfer system. Last year, for example, the school signed a collaborative agreement with Riverland Community College that helps associate’s degree holders from Riverland to go on to complete their bachelor’s degrees online at Minnesota State. Distance-learning and other flexible options are critical for community college students looking to further their careers, she said, because they are often tied to their current communities due to family and other obligations.

“Last year, we created a university-wide work group to focus on improving our transfer work, and this year I’m working with our newly established transfer operations group and an advisory body to implement the group’s recommendations. It’s very important work for many reasons and it’s a good fit for me because I truly believe in education’s power to transform lives. There are many paths to achieve educational goals and ease of transfer can be an important factor.”

She also serves on Minnesota State’s President’s Commission on Diversity and received the group’s Diversity Champion award in 2019.

“That year I was interim associate vice president for undergraduate education. We changed policies, added academic supports, expanded the first-year experience and learning communities, and all of this lead to increased retention and student success. This work was influenced by perspectives I gained from ICI,” she said of the diversity, equity, and inclusion work. “We want paths forward for everyone, but everyone is in need of a little something different to get there.”

The following year, she served as interim provost and vice president of academic and student affairs for Southwest Minnesota State University in Marshall, before returning to Mankato.

If there’s one thing she’s missing today, Wallace said, it’s working directly with students.

“My goal has always been to help students achieve their goals, and as I approach the end of my career, I’ll return to the faculty to do just that,” she said. “For now, I’m focused on growing our research infrastructure, expanding our partnerships with industry and 2-year colleges, enhancing our transfer supports, and extending our continuing education programs and certificates, which help people take smaller steps to get where they want to go. When we accept students, it’s incumbent on us to help them succeed, and that core belief evolved from my years at ICI, too.”