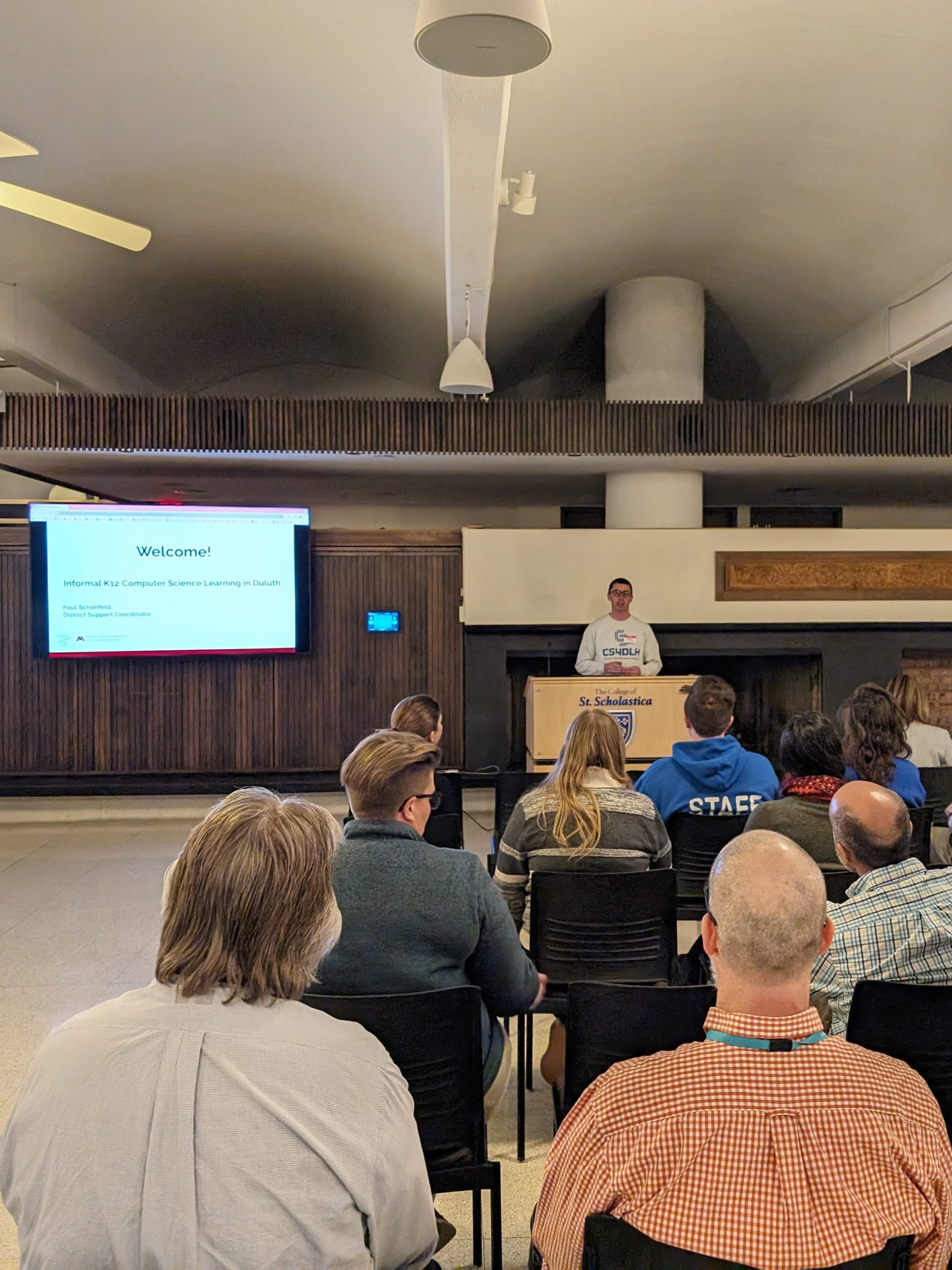

On February 22, the Northern Lights Collaborative for Computing Education hosted an event to share and discuss the 2024 report titled “Informal K12 Computer Science Learning in Duluth.”

The Informal K12 Computer Science Learning in Duluth report is a collaboration among Northern Lights staff, members of the CSforALL Accelerator program, and community leaders in Duluth. Research for the report began in September 2023 with the goal of documenting and analyzing informal Computer Science (CS) learning in Duluth, aiming to raise awareness, foster community connections, and serve as a resource for existing programs. The 2024 report’s lead author is Paul Schonfeld of the Northern Lights Collaborative, with co-authors Jennifer Rosato and Justin Cannady.

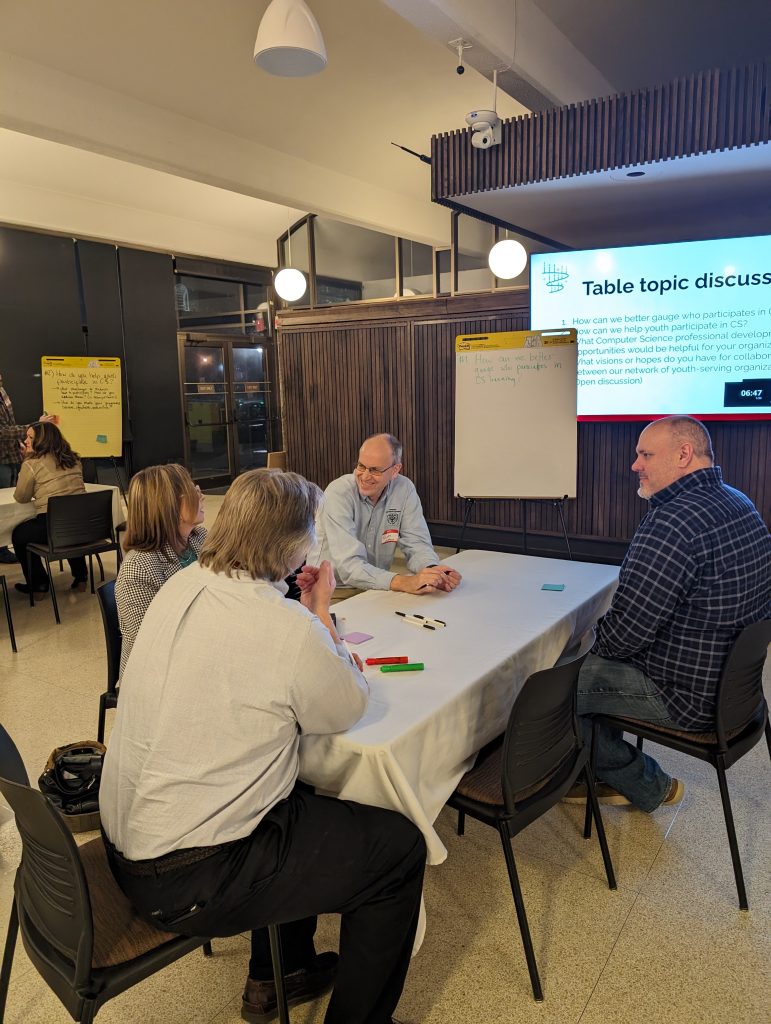

On February 22, a total of 20 participants representing 13 youth-serving organizations gathered at the College of St. Scholastica in Duluth to discuss the report and guide next steps for the project. Guest speaker Emily Saed, director of the MN STEM Ecosystem, presented about the purpose, current projects, and goals for the organization. Participants at the event discussed topics related to the report and recorded ideas on paper to help inform next steps for the project. A summary of the discussions is captured below:

How to gauge participation in computer science

Participants shared ideas of collecting data about CS participation at events like Duluth’s Unity in the Community Event, FIRST robotics events, the Duluth Air Show, youth conferences, or business exposition events. Several organizations highlighted in the report have successful strategies for collecting data about student participation and could be modeled for future efforts. A few model organizations that collect data about participation include STARBASE, Duluth Public Library, and Duluth Public Schools.

How to identify and prevent barriers to participation

Discussions highlighted the need to address transportation challenges for youth to participate in informal CS learning offerings, especially for lower-income populations. Offering CS to all students during school time can help make it more accessible. There are opportunities to integrate CS with other areas including music, art, and as a part of lunch or clubs to help increase participation and help students realize the relevance of CS and how it can be used in creative and useful ways in a variety of contexts.

Desired professional development opportunities

Participants noted that they would like to see professional development offerings that help staff members and volunteers get started with some of the basics of CS, including education around what CS is and introductory experiences to help staff gain confidence. Having time to experiment with CS products would be a helpful component of PD. PD that involves connections to math or other subject-area learning targets would be helpful. Community Education programs may be an avenue for professional development for the broader community.

Visions or hopes for collaborations

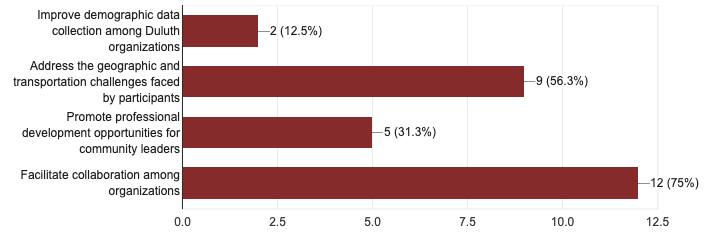

75 percent of attendees who responded to a post-event survey on February 22 indicated that they would prioritize the report recommendation to “facilitate collaboration among organizations.” Other visions and hopes from discussions included inviting youth and industry leaders to future events and organizing a lending library that could include tools, resources, and materials from the various organizations in attendance. The second priority of survey respondents was to address geographic and transportation challenges faced by youth participants (56 percent or respondents said this was a priority).

Which report recommendations do you think we should prioritize?

Figure 1: Recommendation priorities: Event participants highlighted continued collaboration and addressing transportation challenges as areas of focus to be prioritized for this project.

The mission of the Northern Lights Collaborative for Computing Education is to develop evidence-based programs and resources in collaboration with educators and partners that support inclusive K-16 computing education. Northern Lights is coordinating with participants from the February event to help organize more events that support inclusive and equitable computer science learning. The next event for this project will be held in May.

Please email District Support Coordinator, Paul Schonfeld at schon172@umn.edu for more information about this project and report.